"An Eclectic Guide to Trees East of the Rockies" by Glen Blouin

A fun, story-filled guide to our cherished Eastern tree species

The first book I chose to store on the Bioregional Bookshelf is An Eclectic Guide to Trees East of the Rockies, by former New Brunswick resident Glen Blouin. It is nowadays still one of the most relevant, fun-to-read field books about the trees in our region, even though it was written more than twenty years ago.

Being out of print, this book can be found secondhand if you look far enough, or if you’re lucky, maybe even in your local library!

“Trees are apolitical characters — they do not recognize international boundaries. They grow where they are comfortable, where the climate and soils suit them.” (Blouin, p. 8)

Why this is on the shelf

Having somewhat fallen through the cracks of time as many great books sadly do, this one sits on my shelf since the day I found it on an online used book reseller. I find that the histories of trees and shrubs in it are very much timeless and relevant, even in our timeliness-obsessed era. Showing us that the natural world is always current affairs.

It doubles not only as a field guide, but especially as a place to learn about the many fascinating histories, uses and perks of just about every large tree we have here in the Wabanaki-Acadian forest region.

Author & Editor profile

I discovered this author through his other book, Weeds of the Woods, which speaks of the various shrubs of New Brunswick. Glen Blouin’s knowledge of our local flora, particularly of the woody-stemmed species, shows through the pages which makes both his books great reads.

However, Blouin sadly passed away in 2021, leaving his two books as sorts of “monuments” to our biodiversity of woody species.

He lived for a long while in Saint-Paul, New Brunswick, next to where I was raised (Kent County). Blouin worked as an environmental journalist, but spent a large part of his life writing about the plants of this region. He interviewed Indigenous elders as part of his work on the uses and value of our native plants and visibly took a lot of time to sink in this knowledge when writing his two books. He won two awards in journalism from the Canadian Forest Service, in 2003 and 2004 (Source).

The Canadian editor, Boston Mills Press, went out of business in the early 2000s and got absorbed by Firefly Books much later. However, the book is not sold new anymore.

The Layout

The first pages are arranged as an identification guide. The many names are well-put together and constitute a good way to recognize the trees from memory and to learn new ways of speaking. We see the English, scientific and French names (alternate idioms included), with various Indigenous languages’ words added depending on the tree.

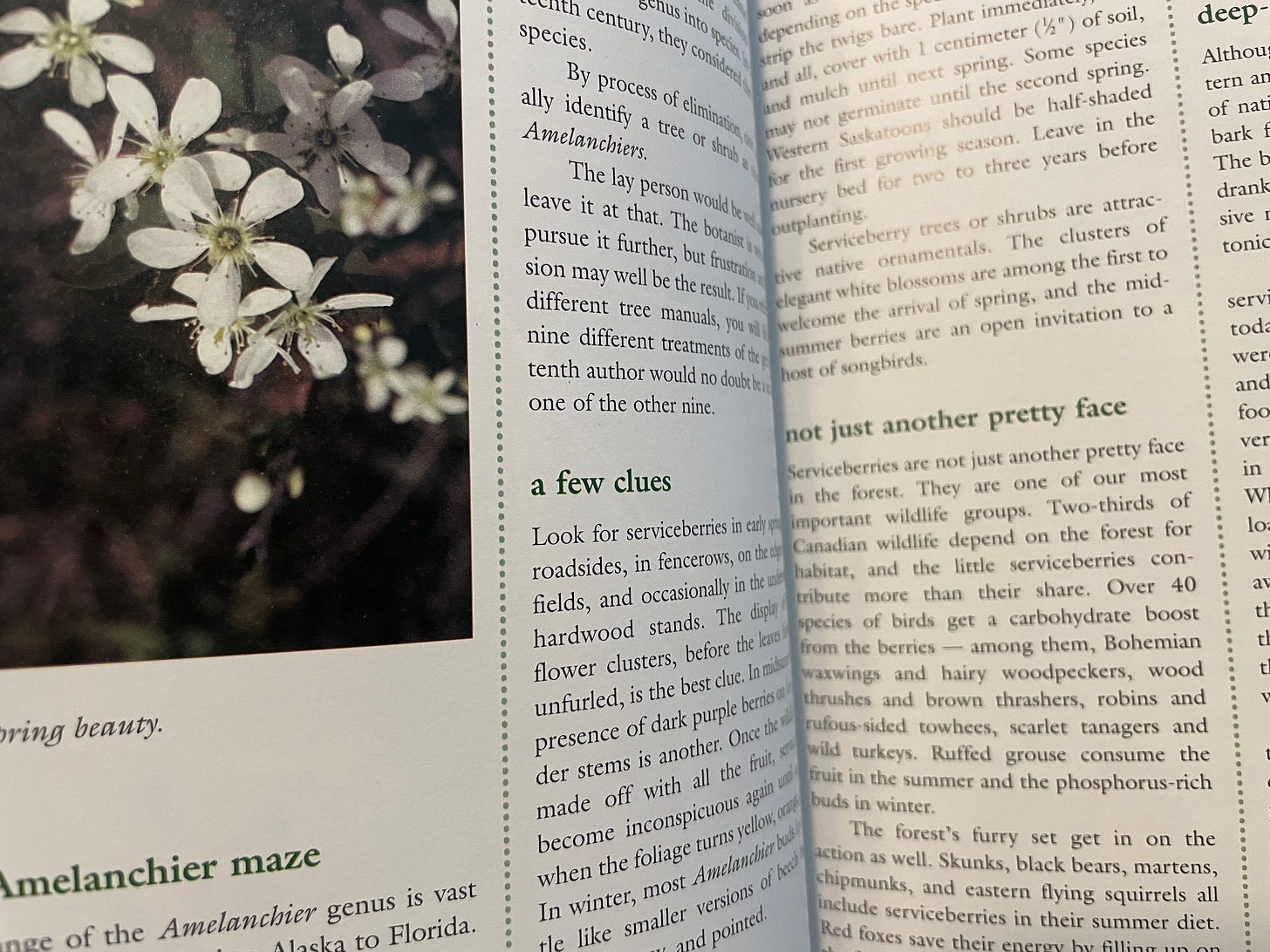

Photos are descriptive and depict various aspect of the trees in many seasons. The text in the following pages, however, is the book’s greatest strength. Herein lies vivid, colourful language, with a bit of humour sprinkled in, explaining the various usages and benefits to nature and humans. Sometimes there are six pages of this additional information with photos!

“Willows are subject to a motley crew of insects (…) Perhaps the most curious is a gall-forming midge that lays its eggs on new growth in the spring; its larvae develop a golf ball-sized gall at the end of the twig. In summer the gall looks like a miniature green cabbage, but by winter it takes on the appearance of a woody jack pine cone. Yes, only conifers bear real cones.” (Blouin, p. 241)

Fieldnotes

Though the scope might seem broad, being East of the Rockies, this book was written by a New Brunswick resident and seems specific to Canada, or at least the Northern US. For us Wabanaki-Acadian forest residents, the book has a great selection of big and small woody plants native to our region and has often four to six pages per feature, which is rare for a field guide.

I find more conventional, (shall we say non-eclectic?) field guides do not have backstory, keeping themselves to the essentials of identifying plants. And they’re there for good reason. But for this one, I have to say the identification stays a bit descriptive; that part is more destined for the advanced botany enthusiast, as there are no drawings. But for the tree-lore alone, this is a worthwhile read.

“What does one get for the child who has everything? A young living tree, and a little help in planting it, is a gift that will be remembered for generations. Since the life expectancy of white pine is 200 to 400 years, that translates into quite a number of generations.” (Blouin, p. 177)

Our trees have always existed here since the melting of the glaciers, and everyone deserves to know their story. That is why Glen Blouin’s book stands out as part of our history and as a way to preserve knowledge that might just be lost if we don’t pay close attention to where we’re going. Thus, I do think that every region needs its Eclectic Guide to Trees!