Human nature and the eclipse : a journal

A total solar...-coaster of emotions, and why I'm not traveling to live another one

Let’s take the long view here : this was an unprecedented event for North America. Not only for the sheer number of individuals present in the path, but for the amount of people just… caring. Every eclipse is really special for a lot of people, at least since we’ve been able to predict these with the accuracy of a clock. But why, do you say, is this predictive behaviour more special than a grand celestial event? Let’s explore my thoughts on that.

I am no expert on human nature, but the latter is 100% what stood out about the 2024 eclipse.

I think it’s linked to anticipation. It’s linked to how mindful most of us that lived through it become, during that specific totality moment that you know will become a core memory. A thing I’m sure no other animal can do. A lot of us gave ourselves a place in our lives to deeply pay attention to a particular moment.

Let me explain.

A CBS Special Report on the 1970 solar eclipse (click to see video) showed there were few areas in the North unhindered by clouds.

— Well Dr. Franklin, uh, I guess the clouds defeated us for most of this path.

—News Anchor

— Well, that is normal for eclipse observation, sir.

—Dr. Franklin

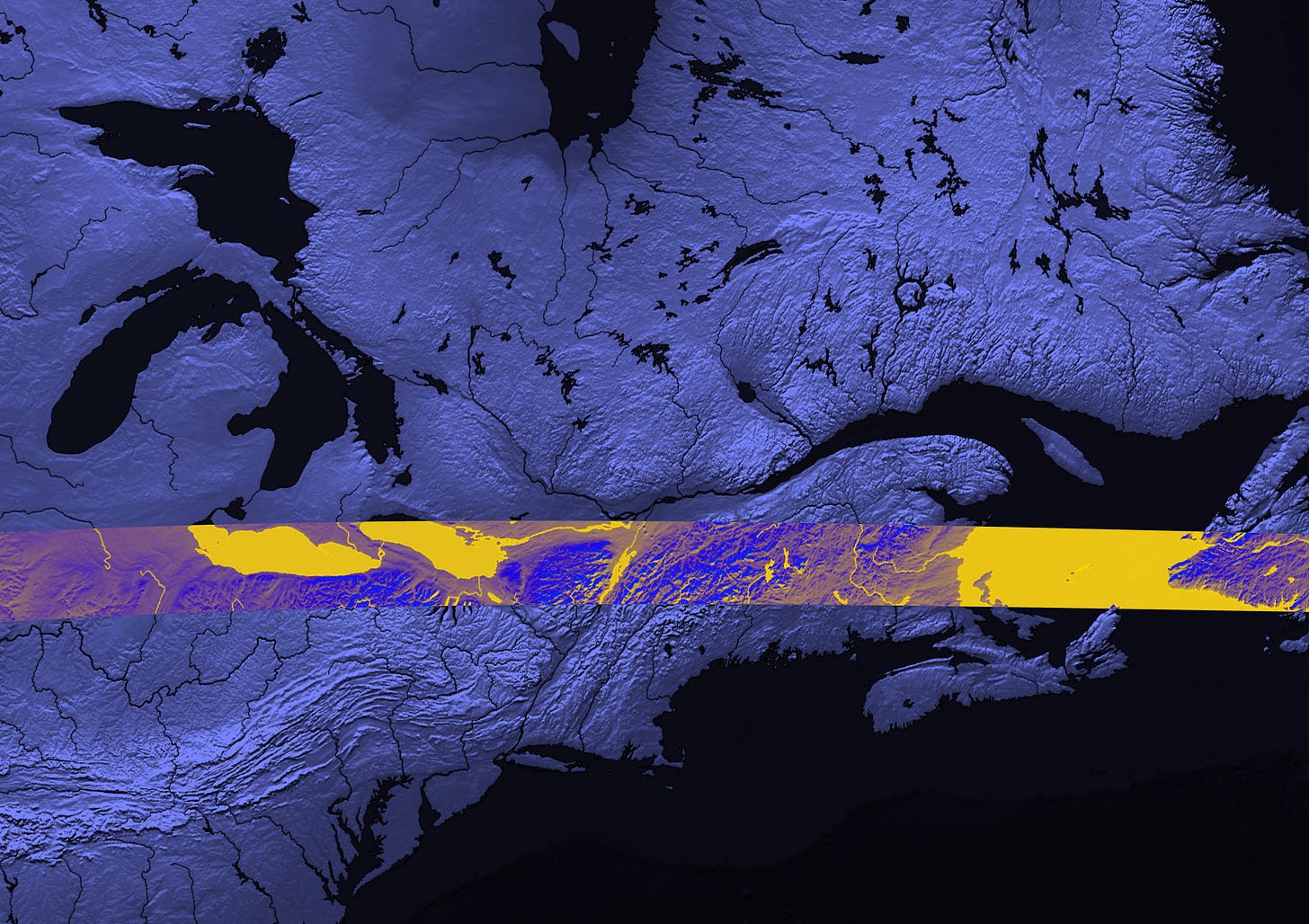

The path of totality would not touch much land again, apart from the Southeast of the U.S. and Mexico.

This made us in the East Coast, living within driving distance of an eclipse, very lucky to have this opportunity.

On April 8, 2024, I spent the totality fully in the moment, and I do not regret it. But I wouldn’t have been too angry if I missed it.

Nothing prepared us for this, apart from our own measuring tools. Not even our evolutionary history as a species; I can’t think of an example where animals adjusts their evolutionary schedules to things that surpass their lives.

For reference, even if evolution took into account eclipses, what would animals benefit from it? Would the family of geese I saw on the lake still float on, unhindered? Probably. It’s no big deal for them, you know, just the moon passing by. The real big deal, this year, are the dual cicada broods having some amazing timing.

Eclipses, Cicadas and Humans, Oh My!

Periodical cicadas, man. These bugs spend 99.9 % of their lives underground. Then, they abruptly emerge, scream, find a mate, and die.

Brood XIII and Brood XIX are going to appear at the same time in 17 states of the USA. These, respectively known as 13- and 17-year cicadas, will emerge as a thousand billion—a trillion—individuals.

This is a whopping year for Turtle Island. Imagine the amount of meat just lying around for all the animals! A real buffet.

This is different than the eclipse, and much rarer. But what’s the most impressive is how the cicadas probably came to evolve that way.

“(…) it is believed that periodical cicadas satiate their predators as an evolutionary strategy: their overwhelming numbers ensure that enough adults will survive predation to successfully mate and lay eggs.” (Britannica)

Also, animals cannot evolve to rely on these bugs as a food source. No animal has really filled the ecological niche to eat these insects, as 13 and 17 years is too long for any animal for it to be more than a once-in-a-lifetime, or even rarer, opportunity (specialist wasps definitely do not live more than a decade old).

Basically, animals like ants and crows benefit a lot more from this than the eclipse. We probably would too, if we ate bugs. For us, though, seeing all those cicadas hang around is going to be little more than a hindrance.

All that to say, regarding the eclipse, evolution surely couldn’t prepare us for a several-decades-apart, once-in-a-lifetime event. As a kind of proof, look at the way our eyes take in the light when they’re fully dilated during darkness.

Only our most extreme calculations could prepare us.

But as someone not especially afraid of insects, I’d be somehow more fearful of the eclipse if I was living in the Midwest, where the three phenomena all converge.

Visions of losing vision

Losing eyesight is my biggest fear, and as a person whose passions are art and nature, these things involve a lot of looking.

So when most people are telling me to not look at the at the sun, the very thing I will drive an hour through solid traffic to look at, an eclipse day is not the most restful day to be alive.

But what calmed me wasn’t only mindfulness. It was definitely the feeling that when it got dark, I was at the right place (in nature), at the right time (not driving through car lines at a snail’s pace) and with the right people (two of my close friends). Being surrounded by life, that may or may not care about this moment, is what made me glad to be there.

My fears went away when I started caring deeply, and when I started looking at the eagle that showed up just before totality.

It’ll happen, no matter what we do.

Clearly, I did not know what to expect. Apart from the ring, the photos I saw from the totality weren’t that cool. And after having lived through it, I’m not going to become an eclipse tourist, or whatever flying around to see night at day is called.

These two photos are respectively from before the eclipse, and from last August, when I went to that exact same spot.

Doesn’t it go to show that we live through amazing moments every day, without realizing it?

What I enjoyed the most about Monday wasn’t the feeling that we were so insignificant. Quite the contrary. A total eclipse make us realize that we are truly capable of something greater than ourselves. When we know something is coming, our species shines for its power to care. And that transcends all boundaries we learned to label to distinguish between ourselves, be they political, social or economic. Our true humanity shines through, and to me, that is the power of being aware, and caring about things.

Mindfulness might not be a silver bullet, but radically caring about things sure helps to form core memories and have fun. Drawing sunsets can help. Field recordings, for those musically inclined. Even nature journaling and poetry, why not.

“One way to open your eyes is to ask yourself, ‘What if I had never seen this before? What if I knew I would never see it again?”

—Rachel Carson

(Cited by John Muir Laws)

And not only can we protect places with care, we can also protect each other, and our own self.

As for solar eclipses, it will be the only one I’ve lived through, and I’m sure many others will join me in not seeing the ‘night of day’ for the rest of our lives.

Let’s put it that way : what truly counts are the memories we choose to dedicate attention to. Caring is our greatest power. And let’s embrace that fact.