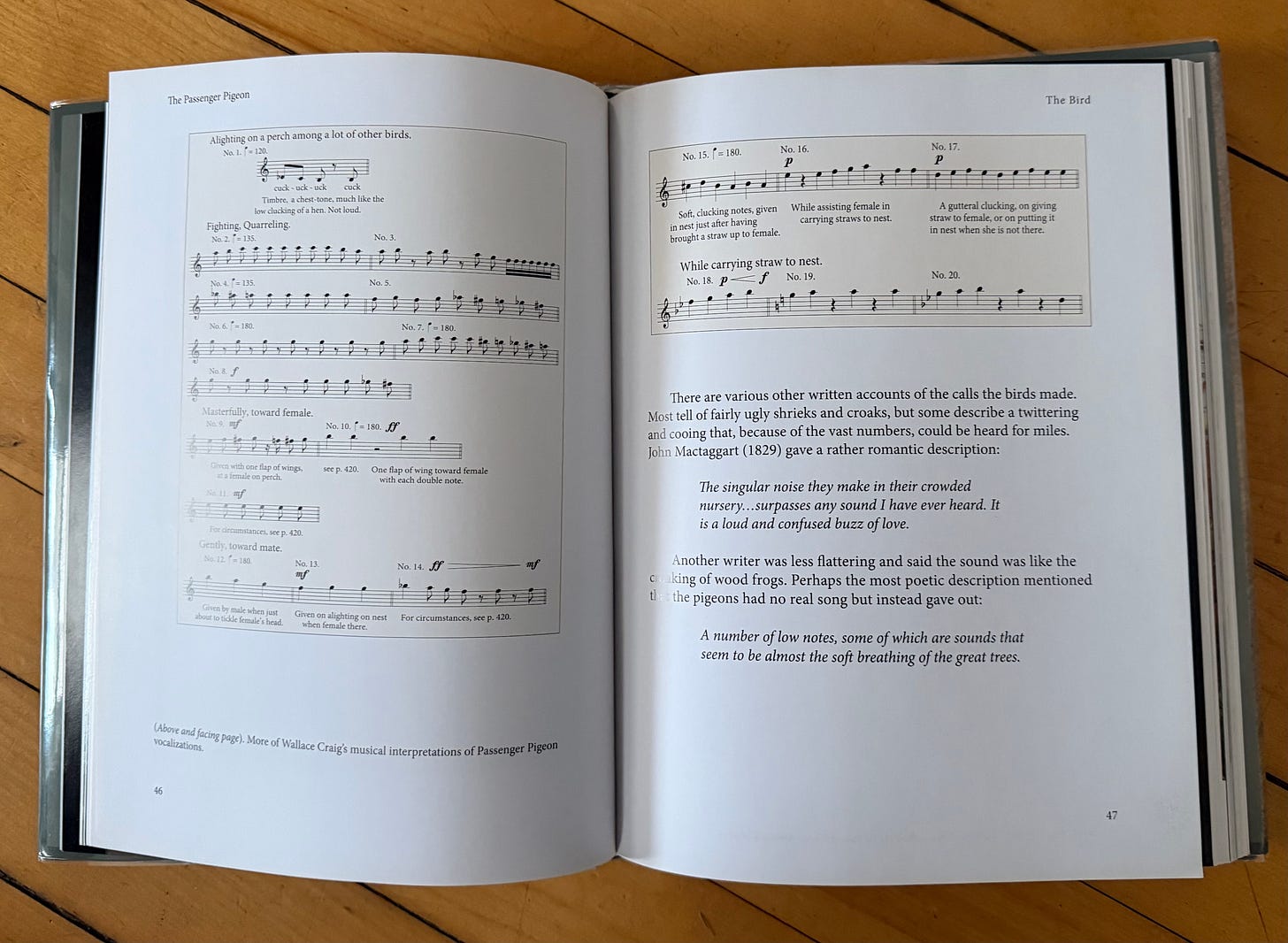

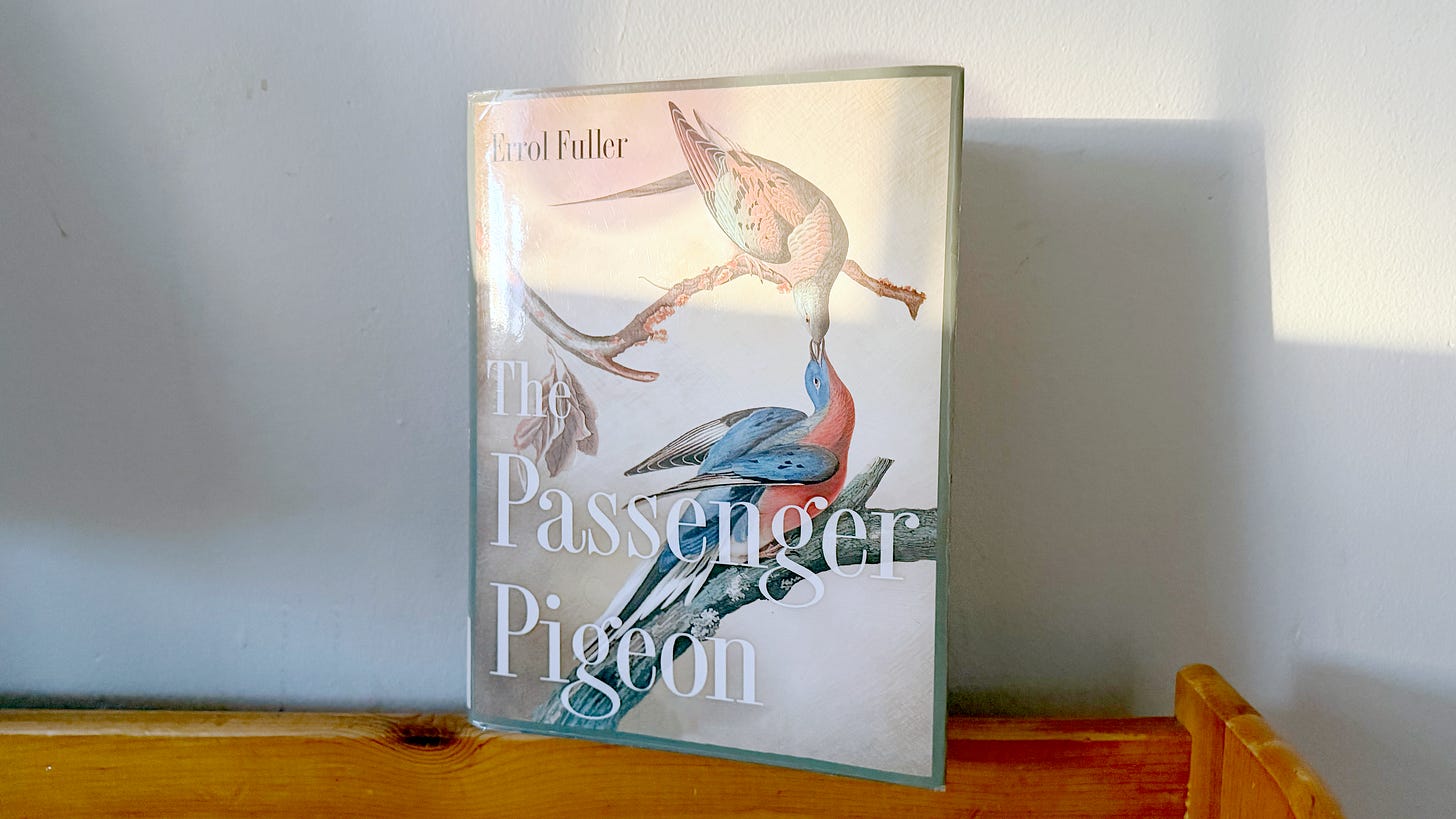

"The Passenger Pigeon" by Errol Fuller

A haunting account of a long-dead bird's decline

Many people have forgotten what was once the most common bird in North America. For centuries, these birds coexisted with settlers, but the lifestyle of the Passenger Pigeon was wholly incompatible with what Errol Fuller calls “The Technological Man”, its agriculture, and its weapons.

The story of this bird is so unbelievable, that Errol Fuller begins his book with “The story of the Passenger Pigeon reads like a work of fiction.” Even though it’s not. Let’s dive into The Passenger Pigeon.

“Basically a streamlined version of the normal rather dumpy pigeon shape, the Passenger Pigeon had very long wings, a long, graduated tail, and a slender body and small head. Clearly, it was designed for speed and endurance while on the wing”

—Fuller, p. 33

If you’ve never heard of this kind of bird, you’re not alone. The Passenger Pigeon has fallen out of memory, outside of ecological and environmental circles. Errol Fuller wishes to dispel many myths about this bird, and does so successfully.

There are three main sections to this book, which has many chapters for quite the short written work. We’ll focus on the first one, the section focused on the bird and the relationship with its environment. The other sections, the appendices and the talk about the birds in captivity, are shorter and more complementary to the main piece. The book can be read in one afternoon, since its 176 pages are full of images, large text and appendices. And it’s what makes this book so great.

But really, have you ever heard of the Passenger Pigeon? Individuals in its flocks were numbering in the thousands, which is impressive for quite large a bird.

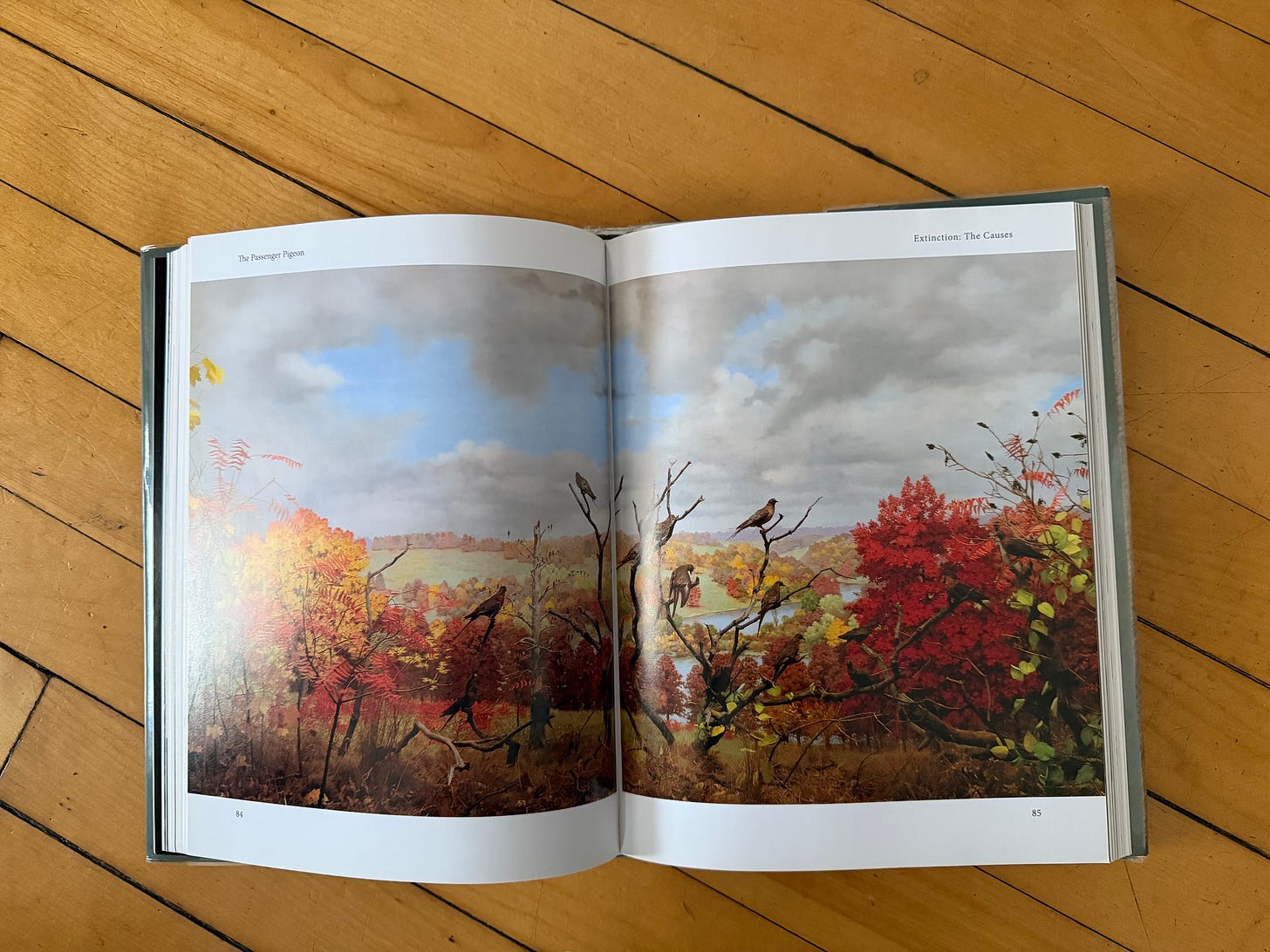

The forests that were once covering Eastern North America were in fact prime habitat for this bird, a nomadic tree-dweller which opportunistically fed on mast crops of American chestnuts, as well as agricultural crops whenever they could lay their beaks on them, or anything else really.

Their flocks would blot out the sun with their sheer magnitude, and would descend upon farmers pitilessly eating all they could find. Here is what Errol Fuller imagined a farmer from 1810 in Pennsylvania would have experienced:

”The growing crops are destroyed, the buds are eaten or trampled, the orchards wrecked. It is too late in the year to plant again, and the harvest that promised so much will now be a disaster. There will be little to feed the family and nothing to sell to local people. Nor will there be anything left for the livestock. The well is fouled, and this will mean a long walk to the river to fetch fresh water.

The damage the birds have wrought can hardly be measured. An entirely new start will be needed -- if, that is, you can survive the next few months and the winter that will follow.”

—Fuller, p. 26

In short, the book makes for a fascinating read, because it talks of a reality that no longer exists, and it does so by focusing on the decline of a species incompatible with the European settler lifestyle.

Its population tipping point was reached in the “second half of the 19th century”, where mass killings were routinely occuring.

A strange habit that brought upon its end

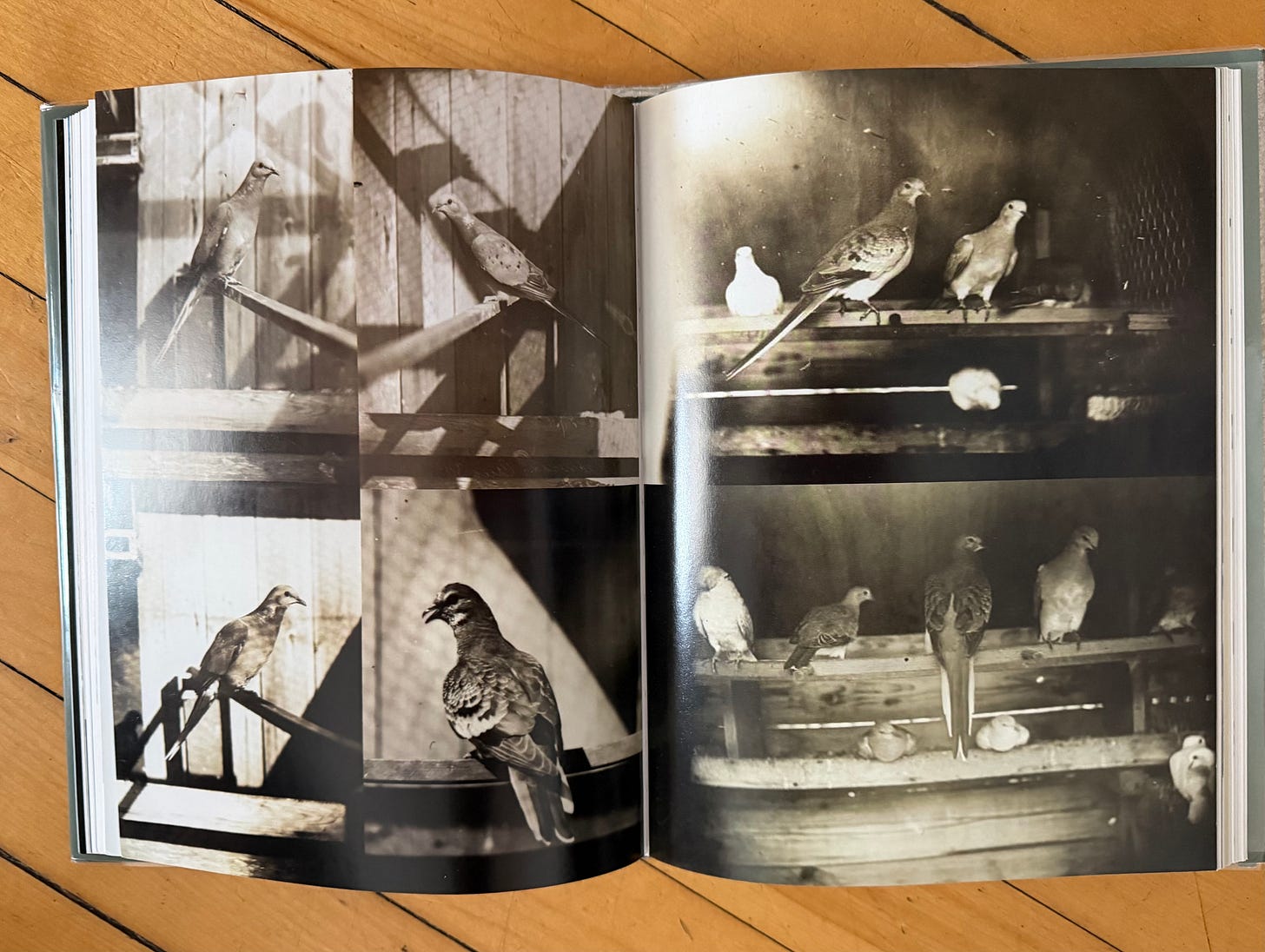

Many things are unknown about this bird, including the amount of eggs per nest, where accounts differ. But one habit that made the Passenger Pigeon particularly easy to hunt was its parental instinct. Or lack thereof.

“When the chicks were around two weeks old the adults just flew off, leaving their offspring alone in the nest. After a while the abandoned creatures simply flopped to the ground, and it was a day or two before they were themselves able to fly off. It is easy to imagine what happened during this brief period. The youngsters were distressingly vulnerable, and mammalian, reptilian, and avian predators would come from miles around to take advantage of these defenseless babies. With the vast number of squabs available, however, this local predatory population soon became sated, and in percentage terms only a small proportion of pigeon chicks were actually consumed.”

—Fuller, p. 83

This habit, in fact, worked for pigeons, in an environment where the predators did not know when or where the flocks would come. A few carnivores, or Indigenous hunters, would easily be overwhelmed by such a large amount of meat. But for the new settler predator, their goal wasn’t necessarily eating. Since they had advanced weapons, “dozens of individuals could be brought down with a single shot from a gun simply pointed skyward”.

The settlers also set up complex netting contraptions where they nested, where they would either cut, burn down trees, use smoke or sulphur to bring the birds down, and then simply break their necks once they get a hold of them.

The “nestings”, or massacres, were particularly macabre: after the time of the nesting in Shelby, Michigan in 1874, when one of the largest massacres occurred, people would still talk of the great flocks as though they were common. It is because that pigeon’s flocks would, according to Errol Fuller, possibly “fool” observers into thinking they were as common as they once were a few decades ago. But the tipping point had already been reached, and the species was doomed. That’s what happens when a society meticulously kills millions of birds at once.

Codependent on primary forests

The most impressive fact about this book’s first part, isn’t necessarily the fact that the pigeons were meticulously killed - it’s that the forest they depended on for food and habitat were all destroyed, and it’s one of the leading reasons why they couldn’t survive today.

”Woodland and forest were removed primarily to make land available for agriculture or townships, but even places that weren’t required for such purposes were subject to habitat destruction as their trees were chopped down for fuel or to provide building materials. (...) Between 1850 and 1910 around 180 million acres were cleared for farming alone.”

—Fuller, p. 83

Many of the forests the birds used, made primarily of American chestnut, are now gone due to the steep decline of that tree. However, the author points out these only started to decline after the introduction of the nursery-introduced Chestnut blight, in 1905, when the flocks of pigeons were long disappeared from the face of the Earth.

It is the strength of the contrast between yesterday and today’s world that makes this book and subject stand out. Our ecology today, in the Eastern Woodland, feels wholly different than what it used to be. And a lot of the pieces—Chestnut, Large Hemlocks, Pigeons—won’t ever come back. The decline and disappearance of the pigeons, for me, marks one of the many tipping points, heralding a new time when humankind controlled the world, rather than the opposite.

And the book’s end, after the pigeons in captivity—poor lonely things who only lasted until 1914—talks about the wonder which pigeons evoked in art.

In this work, Errol Fuller successfully not only evokes wonder in the reader, but also laments the lack of calculated study of the bird’s population before its decline. It was gone before the advent of systematic bird science, and the only accounts of the bird talk about the spectacular nature of its flocks, right up to its decline.

The book stands out as a testament to our power over the natural world, which speaks of the fragility of individual species. Conservation is not only protecting, but also remembering to not repeat the same mistakes as before.

Happy New Year Sam! Great to see you at work. In my mom's estate I almost threw out a box of what looked like broken pieces of a porcelain bowl...turned out they were elephant bird egg shells from an early trip to Madagascar she collected from the beach. Another sad story. I expect there are many, most of which are unpopular or unnoticed by our species, since we tend to only look for utility to us or to get rid of species that annoy us.